The first version of the story is the Tale of Tinúviel, which was written in 1917 as a part of The Book of Lost Tales. During the 1920s, Tolkien started to reshape the tale and to transform it into an epic poem which he called The Lay of Leithian. He never finished it, leaving three of seventeen planned cantos unwritten. After his death, The Lay of Leithian was published in The Lays of Beleriand, together with The Lay of the Children of Húrin and several other unfinished poems. The latest version of the tale is told in prose form in one chapter of The Silmarillion and is recounted by Aragorn in The Fellowship of the Ring. Furthermore, it was the model for "The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen", which is told in the appendices of The Lord of the Rings.

Synopsis

As told in The Silmarillion, the later version of the tale:Beren was the last survivor of a group of Men led by his father Barahir that had still resisted Morgoth, the Dark Enemy, after the Battle of Sudden Flame, in which Morgoth had conquered much of northern Middle-earth. After the defeat of his companions, he fled from peril into the elvish realm Doriath. There he met Lúthien, the only daughter of King Thingol and Melian the Maia, as she was dancing and singing in a glade. Upon seeing her Beren fell in love, for she was the fairest of all elves. She later fell in love with him as well, when he, moved by her beauty and enchanting voice, gave her the nickname "Nightingale." As Thingol disliked Beren and regarded him as being unworthy of his daughter, he set a seemingly impossible task on Beren that he had to achieve before he could marry Lúthien. Thingol asked Beren to bring him one of the Silmarils, the three hallowed jewels made by Fëanor, which Morgoth had stolen from the elves.

Beren left Doriath and set out on his quest to Angband, the enemy’s fortress. Although Thingol tried to prevent it, Lúthien later followed him. On his journey to the enemy’s land Beren reached Nargothrond, an Elvish stronghold, and was joined by ten warriors under the lead of King Finrod, who had sworn an oath of friendship to Beren's father. Although Fëanor’s sons, Celegorm and Curufin, warned them not to take the Silmaril that they considered their own, the company was determined to accompany Beren. On their way to Angband they were seized by the servants of Sauron, despite the best efforts of Finrod to maintain their guise as Orcs, and imprisoned in Tol-in-Gaurhoth. One by one they were killed by a werewolf until only Beren and Finrod remained. When the wolf went for Beren, Finrod broke his chains and wrestled it with such fierceness that they both died.

When she was following Beren, Lúthien was captured and brought to Nargothrond by Celegorm and Curufin. Aided by Huan, Celegorm’s hound (which according to prophecy could only be defeated by the greatest werewolf ever), she was able to flee. With his aid, she came to Sauron’s fortress where Huan defeated the werewolves of the Enemy, Draugluin the sire of werewolves, and Sauron himself in wolf-form. Then Lúthien forced Sauron to give ownership of the tower to her. She freed the prisoners, among them Beren. Meanwhile, Sauron took the form of a vampire and fled to Taur-nu-Fuin.

Anke-Katrin Eiszmann

Beren wanted to try his task once more alone, but Lúthien insisted on coming with him. However, they are attacked by Celegorm and Curufin, who have been exiled from Nargothrond. Beren was wounded by Curufin, but Lúthien healed him. Through magic, they took the shapes of the bat Thuringwethil and the wolf Draugluin that Huan had killed. Thereby they were able to enter the enemy’s land and at last came to Angband and before Morgoth’s throne. There Lúthien sang a magical song which made the Dark Lord and his court fall asleep; then Beren cut a Silmaril from Morgoth’s crown. As he tried to cut out the others, his knife broke and a shard glanced off Morgoth's face, awakening him. As they attempted to leave, the gate was barred by Carcharoth, a giant werewolf, who was bred as an opponent to Huan. He bit off and swallowed Beren’s hand, in which Beren was holding the Silmaril. Carcharoth was burned by the pure light of the Silmaril and ran off madly. Eagles then helped Beren and Lúthien escape.Beren and Lúthien returned to Doriath, where they told of their deeds and thereby softened Thingol’s heart. He accepted the marriage of his daughter and the mortal Man, although Beren’s task had not been fulfilled. Beren and Huan participated in the hunt for Carcharoth, who in his madness had come into Doriath and caused much destruction there. Both of them were killed by the wolf, but Carcharoth was also slain. Before he died, Beren handed the Silmaril, which was recovered from Carcharoth's belly, to Thingol.

Luthien and Beren by highlandheart1968

Grieving for Beren, Lúthien also died, and came to the halls of Mandos. There she sang of her ill fate, that she would never again see Beren, who as a mortal Man had passed out of the world. Thereby Mandos was moved to pity. He restored Beren and Lúthien to life and granted mortality to the Elf. Lúthien left her home and her parents and went to Ossiriand with Beren. There they dwelt for the rest of their lives, and both eventually died the death of mortal Men.

Significance in the legendarium

After the recovery of the Silmaril by Beren and Lúthien, many people of Middle-earth sought to possess it, and there were wars between the Sindar, the Noldor and the Dwarves, in which the Sindar were defeated. The Silmaril was taken by Eärendil, who sailed to Valinor with it and persuaded the Valar to make war on Morgoth, which led to the latter's defeat in the War of Wrath.The marriage of Beren and Lúthien was the first of the three unions of a mortal Man and an Elf, of which came the Half-elven, those who had both elven and human ancestry. Like Lúthien, they were given the choice of being counted among either Elves or Men. The extended live-action film of The Fellowship of the Ring would make this connection through a song Aragorn sings at night in Elvish. When questioned by Frodo, he simply explains that it relates to an Elven woman who gave up her immortality for the love of a man.

Inspiration

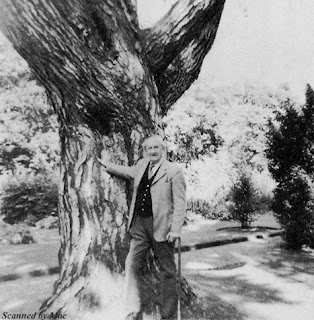

The Tale of Beren and Lúthien was regarded as the central part of his legendarium by Tolkien. The story and the characters reflect the love of Tolkien and his wife Edith. Particularly, the event when Edith danced for him in a glade with flowering hemlocks seems to have inspired his vision of the meeting of Beren and Lúthien. Also, some sources indicate that Edith's family disapproved of Tolkien originally, due to his being a Catholic. On Tolkien's grave, J. R. R. Tolkien is referred to as Beren and Edith, as Lúthien.The tale of Beren and Lúthien also shares an element with folktales such as the Welsh Culhwch and Olwen, maybe its main literary inspiration, and the German The Devil With the Three Golden Hairs and The Griffin— namely, the disapproving parent who sets a seemingly impossible task (or tasks) for the suitor, which is then fulfilled. The hunting of Carcharoth the Wolf may be inspired by the hunting of the giant boar Twrch Trwyth in Culhwch and Olwen or other hunting legends. The quest for one of the three Silmarils from the Iron Crown of Morgoth has a close parallel in the search for the three golden hairs in the head of the Devil. The sequence in which Beren loses his hand to the Wolf may be inspired by the god Tyr and the wolf Fenrir, characters in Norse mythology. Tolkien also got inspiration from the great love story of Romeo and Juliet.

Dior Eluchíl, son of Beren and Lúthien.

Source HERE

The names of Beren and Luthien are on the Tolkiens gravestone.

Love and light,

Trace

xoxo