The Faery Witch

Describes one who lived in Innis Sark:--"He never touched beer, spirits, or meat in all his life, but has lived entirely on bread, fruit. and vegetables. A man who knew him thus describes him--'Winter and summer his dress is the same--merely a flannel shirt and coat. He will pay his share at a feast, but neither eats nor drinks of the food and drink set before him. He speaks no English, and never could be made to learn the English tongue, though he says it might be used with great effect to curse one's enemy. He holds a burial-ground sacred, and would not carry away so much as a leaf of ivy from a grave. And he maintains that the people are right to keep to their ancient usages, such as never to dig a grave on a Monday, and to carry the coffin three times round the grave, following the course of the sun, for then the dead rest in peace. Like the people, also, he holds suicides as accursed; for they believe that all its dead turn over on their faces if a suicide is laid amongst them.

"'Though well off, he never, even in his youth, thought of taking a wife; nor was he ever known to love a woman. He stands quite apart from life, and by this means holds his power over the mysteries. No money will tempt him to impart his knowledge to another, for if he did he would be struck dead--so he believes. He would not touch a hazel stick, but carries an ash wand, which he holds in his hands when he prays, laid across his knees; and the whole of his life is devoted to works of grace and charity, and though now an old man, he has never had a day's sickness. No one has ever seen him in a rage, nor heard an angry word from his lips but once, and then being under great irritation, he recited the Lord's Prayer backwards as an imprecation on his enemy. Before his death he will reveal the mystery of his power, but not till the hand of death is on him for certain.'" When he does reveal it, we may be sure it will be to one person only--his successor. There are several such doctors in County Sligo, really well up in herbal medicine by all accounts, and my friends find them in their own counties.

All these things go on merrily. The spirit of the age laughs in vain, and is itself only a ripple to pass, or already passing away.

The spells of the witch are altogether different; they smell of the grave. One of the most powerful is the charm of the dead hand. With a hand cut from a corpse they, muttering words of power, will stir a well and skim from its surface a neighbour's butter.

A candle held between the fingers of the dead hand can never be blown out. This is useful to robbers, but they appeal for the suffrage of the lovers likewise, for they can make love-potions by drying and grinding into powder the liver of a black cat. Mixed with tea, and poured from a black teapot, it is infallible. There are many stories of its success in quite recent years, but, unhappily, the spell must be continually renewed, or all the love may turn into hate. But the central notion of witchcraft everywhere is the power to change into some fictitious form, usually in Ireland a hare or a cat.

Long ago a wolf was the favourite. Before Giraldus Cambrensis came to Ireland, a monk wandering in a forest at night came upon two wolves, one of whom was dying. The other entreated him to give the dying wolf the last sacrament. He said the mass, and paused when he came to the viaticum. The other, on seeing this, tore the skin from the breast of the dying wolf, laying bare the form of an old woman. Thereon the monk gave the sacrament. Years afterwards he confessed the matter, and when Giraldus visited the country, was being tried by the synod of the bishops. To give the sacrament to an animal was a great sin. Was it a human being or an animal? On the advice of Giraldus they sent the monk, with papers describing the matter, to the Pope for his decision. The result is not stated.

Giraldus himself was of opinion that the wolf-form was an illusion, for, as he argued, only God can change the form. His opinion coincides with tradition, Irish and otherwise.

It is the notion of many who have written about these things that magic is mainly the making of such illusions. Patrick Kennedy tells a story of a girl who, having in her hand a sod of grass containing, unknown to herself, a four-leaved shamrock, watched a conjurer at a fair. Now, the four-leaved shamrock guards its owner from all pishogues (spells), and when the others were staring at a cock carrying along the roof of a shed a huge beam in its bill, she asked them what they found to wonder at in a cock with a straw. The conjurer begged from her the sod of grass, to give to his horse, he said. Immediately she cried out in terror that the beam would fall and kill somebody.

This, then, is to be remembered--the form of an enchanted thing is a fiction and a caprice.

Source

Fairy witch trials of Sicily

The Fairy witch trials of Sicily, were conducted on Sicily between the late 16th and middle of the 17th centuries. They represent a unique phenomenon, as in this area,

witch trials involved the mythological fairies from folklore. (Link above)

In Sicily, there was a belief that the elves or fairies would make contact with humans, mostly women, whom they took to Benevento, the Blockula of Sicily. The fairies were called donas de fuera, which was also a name for the women who associated with them. The fairies where described as beauties dressed in white, red or black; they could be male or female, and their feet were the paws of cats, horses or of a peculiar "round" shape. They came in groups of five or seven and a male fairy played the lute or the guitar while dancing. The fairies and the humans were divided into companies in different sizes (different ones for noble and non-noble humans), under the lead of an ensign.

Fairy Investigation Society

The Fairy Investigation Society was founded in Britain in 1927 by a Sir Quentin Craufurd, MBE, to collect information on fairy sightings. In 1983, a headquarters for the society was located in Blackrock, Dublin, Ireland. During its prime, the society organized meetings, lectures, and discussions for collecting evidence of fairy life. With the outbreak of WW2, however, members were dispersed and the society’s records were largely lost or destroyed during the conflict. The society then became inactive for a while. In 1955, with a new and energetic secretary, the society was revived and began to issue a regular newsletter. The newsletter had a listing of reports from members or other individuals. The society also sent out brochures to recruit new members. During the late 1950s, there were at least fifty members, including famous people such as author Alasdair Alpin MacGregor, Ithell Colquhoun, Leslie Alan Shepard, Hugh Dowding, Walter Starkie (of gypsy lore fame), and animator Walt Disney. As the society grew and became more well-known, newspaper articles ridiculing the sightings and study of fairies appeared. They claimed fairies were only a superstition of past centuries. The society once again became inactive.

As late as 1990, a society of the same name is rumored to be active.

Beachcombing - Fairy gifts

Beachcombing has sometimes lamented in this place the passing of the fairy faith be that in Essex, the Isle of Man or Yorkshire. How refreshing then to learn that in one corner of Europe the locals still walk in terror of the little folk. Beachcombing refers, of course, to the town of Bolgunjarvik in north-western Iceland where a couple of months ago the fairies were reportedly bombarding the community with rocks and soil in revenge for some inconsiderate dynamiting!

Readers will be glad to hear that fairy mediators have been sent in to restore human-fairy relations.

This set Beachcombing thinking of a rare subcategory of the fairy faith, what might be called ‘fairy gifts’: shoes, clothes, flags and other treasures from under the sidh hills.

Beach starts in Iceland itself with the textile named: ‘The fairy woman’s cloth of Burstafjall’. He can do no better than quote Invisible who wrote in some months ago about this extraordinary object:

According to legend, the wife of the district police superintendent and public prosecutor at the farm of Burstafjall in Vopnafjordur in the east of Iceland , received this cloth as payment from a fairy woman whom she had midwifed. The cloth is now in the National Museum in Rekjavik. Thor Magnusson, who is the president’s Custodian of Antiquities says, ‘Certainly it’s a unique cloth, but it often happened in the old days that if people did not remember, or could not explain, the true origin of a rare item, they claimed that fairies had made it.’ [Sydvenska Dagbladet Snallposten 5 August 1984].

It would be lovely to find a picture of this object.

There are some other ‘gifts’ too up and down the Atlantic coast of Europe including Beachcombing’s favourite manifestation of fairy, the flag of MacLeod (pictured above), kept today at Dunvegan Castle. Textile experts long ago spoilt the fun pronouncing that the flag is made of silk and that as such it has an eastern origin: perhaps it was a gift brought back from the crusades? Again there is an object of forgotten origins, explained by magic. But in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the flag was believed to bring luck to the clan and one member of the Clan MacLeod even brought

a picture of the flag on bombing raids in the Second World War…

The most famous object south of the border is probably the Luck of Eden Hall, a cup that was won from the fairies by a member of the Musgrove family ‘before records began’ and that today stands, intact, in the Victoria and Albert Museum. The cup, which is astoundingly beautiful, is supposed to be of ‘eastern origin’: crusades again anyone?

Beachcombing was going to mount a desperate attempt in defence of this particular object but he then learnt that the letters IHS are embossed on the casing.

Fairies are many things, but church-goers they are most certainly not.

There are also, of course, Neolithic arrow heads that used to be known as ‘fairy arrows’ and that were blamed for various cattle illnesses when discovered out in the fields.

Then Invisible who deserves the credit for almost all of the material gathered here came across a fairy shoe from Ireland:

It was found by a farm labourer on the Beara Peninsula, south-west Ireland, in 1835. It is black, worn at the heel and styled like that of an eighteenth-century gentleman. But it is also only two and seven-eights inches long and seven-eights of an inch at its widest – too long and narrow even for a doll’s shoe. If it were an apprentice piece, say, how did it come to be found on a remote sheep track? Why was it made in the style of the previous century? Why is it such an odd shape? How did it come to be worn?… The man who found the shoe assumed it belonged to the ‘little people’ and gave it to the local doctor, from whom it passed to the Sommerville family of Castletownshend, County Cork. On a lecture tour of America, the author Dr. Edith Sommerville. gave the shoe to Harvard University scientists, who examined it minutely. The shoe had tiny hand-stitches and well-crafted eyelets (but no laces), and ‘was thought to be’ of mouse skin.

Beach ran across the following reference in a nineteenth-century book.

He would KILL and PAY for an advert and described from a nineteenth-century Irish newspaper.

Are you aware that, on this side of the channel [i.e in Ireland], we have so little doubt of the existence of fairies, that it is no uncommon occurrence to see shoes of fairy manufacture publicly advertised in the newspapers? If I tell you, that while crossing a field, in the purple light of the morning, the attention of a peasant was arrested by the sound of a shoemaker’s hammer; and that, upon leaving the path to discover the cause, he disturbed an elfin cobbler, who it seems was at his trade betimes, and mending his brogues by the side of the ditch ; that the spirit of the air, anxious to escape from the prying eyes of mortal wight, leapt from the bank, and, in his haste, dropped both shoe and hammer: if I go on to tell you, that this story is most gravely related, and that the editor informs the public, that both shoe and hammer were carried to such a house, in such a street, in a certain town, in the county of Roscommon, and may there be viewed by any curious or incredulous persons; you will, I think, acknowledge that my tale has at least a better foundation than many which are related to our disadvantage, and but too readily

swallowed by the credulity of our English friends.

I hope you found these collections of folk lore as interesting as I :0)

Love & light

Trace

xoxo

Fairy witch trials of Sicily

The Fairy witch trials of Sicily, were conducted on Sicily between the late 16th and middle of the 17th centuries. They represent a unique phenomenon, as in this area,

witch trials involved the mythological fairies from folklore. (Link above)

In Sicily, there was a belief that the elves or fairies would make contact with humans, mostly women, whom they took to Benevento, the Blockula of Sicily. The fairies were called donas de fuera, which was also a name for the women who associated with them. The fairies where described as beauties dressed in white, red or black; they could be male or female, and their feet were the paws of cats, horses or of a peculiar "round" shape. They came in groups of five or seven and a male fairy played the lute or the guitar while dancing. The fairies and the humans were divided into companies in different sizes (different ones for noble and non-noble humans), under the lead of an ensign.

Fairy Investigation Society

The Fairy Investigation Society was founded in Britain in 1927 by a Sir Quentin Craufurd, MBE, to collect information on fairy sightings. In 1983, a headquarters for the society was located in Blackrock, Dublin, Ireland. During its prime, the society organized meetings, lectures, and discussions for collecting evidence of fairy life. With the outbreak of WW2, however, members were dispersed and the society’s records were largely lost or destroyed during the conflict. The society then became inactive for a while. In 1955, with a new and energetic secretary, the society was revived and began to issue a regular newsletter. The newsletter had a listing of reports from members or other individuals. The society also sent out brochures to recruit new members. During the late 1950s, there were at least fifty members, including famous people such as author Alasdair Alpin MacGregor, Ithell Colquhoun, Leslie Alan Shepard, Hugh Dowding, Walter Starkie (of gypsy lore fame), and animator Walt Disney. As the society grew and became more well-known, newspaper articles ridiculing the sightings and study of fairies appeared. They claimed fairies were only a superstition of past centuries. The society once again became inactive.

As late as 1990, a society of the same name is rumored to be active.

Beachcombing - Fairy gifts

Beachcombing has sometimes lamented in this place the passing of the fairy faith be that in Essex, the Isle of Man or Yorkshire. How refreshing then to learn that in one corner of Europe the locals still walk in terror of the little folk. Beachcombing refers, of course, to the town of Bolgunjarvik in north-western Iceland where a couple of months ago the fairies were reportedly bombarding the community with rocks and soil in revenge for some inconsiderate dynamiting!

Readers will be glad to hear that fairy mediators have been sent in to restore human-fairy relations.

This set Beachcombing thinking of a rare subcategory of the fairy faith, what might be called ‘fairy gifts’: shoes, clothes, flags and other treasures from under the sidh hills.

Beach starts in Iceland itself with the textile named: ‘The fairy woman’s cloth of Burstafjall’. He can do no better than quote Invisible who wrote in some months ago about this extraordinary object:

According to legend, the wife of the district police superintendent and public prosecutor at the farm of Burstafjall in Vopnafjordur in the east of Iceland , received this cloth as payment from a fairy woman whom she had midwifed. The cloth is now in the National Museum in Rekjavik. Thor Magnusson, who is the president’s Custodian of Antiquities says, ‘Certainly it’s a unique cloth, but it often happened in the old days that if people did not remember, or could not explain, the true origin of a rare item, they claimed that fairies had made it.’ [Sydvenska Dagbladet Snallposten 5 August 1984].

It would be lovely to find a picture of this object.

There are some other ‘gifts’ too up and down the Atlantic coast of Europe including Beachcombing’s favourite manifestation of fairy, the flag of MacLeod (pictured above), kept today at Dunvegan Castle. Textile experts long ago spoilt the fun pronouncing that the flag is made of silk and that as such it has an eastern origin: perhaps it was a gift brought back from the crusades? Again there is an object of forgotten origins, explained by magic. But in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the flag was believed to bring luck to the clan and one member of the Clan MacLeod even brought

a picture of the flag on bombing raids in the Second World War…

The most famous object south of the border is probably the Luck of Eden Hall, a cup that was won from the fairies by a member of the Musgrove family ‘before records began’ and that today stands, intact, in the Victoria and Albert Museum. The cup, which is astoundingly beautiful, is supposed to be of ‘eastern origin’: crusades again anyone?

Beachcombing was going to mount a desperate attempt in defence of this particular object but he then learnt that the letters IHS are embossed on the casing.

Fairies are many things, but church-goers they are most certainly not.

There are also, of course, Neolithic arrow heads that used to be known as ‘fairy arrows’ and that were blamed for various cattle illnesses when discovered out in the fields.

Then Invisible who deserves the credit for almost all of the material gathered here came across a fairy shoe from Ireland:

It was found by a farm labourer on the Beara Peninsula, south-west Ireland, in 1835. It is black, worn at the heel and styled like that of an eighteenth-century gentleman. But it is also only two and seven-eights inches long and seven-eights of an inch at its widest – too long and narrow even for a doll’s shoe. If it were an apprentice piece, say, how did it come to be found on a remote sheep track? Why was it made in the style of the previous century? Why is it such an odd shape? How did it come to be worn?… The man who found the shoe assumed it belonged to the ‘little people’ and gave it to the local doctor, from whom it passed to the Sommerville family of Castletownshend, County Cork. On a lecture tour of America, the author Dr. Edith Sommerville. gave the shoe to Harvard University scientists, who examined it minutely. The shoe had tiny hand-stitches and well-crafted eyelets (but no laces), and ‘was thought to be’ of mouse skin.

Beach ran across the following reference in a nineteenth-century book.

He would KILL and PAY for an advert and described from a nineteenth-century Irish newspaper.

Are you aware that, on this side of the channel [i.e in Ireland], we have so little doubt of the existence of fairies, that it is no uncommon occurrence to see shoes of fairy manufacture publicly advertised in the newspapers? If I tell you, that while crossing a field, in the purple light of the morning, the attention of a peasant was arrested by the sound of a shoemaker’s hammer; and that, upon leaving the path to discover the cause, he disturbed an elfin cobbler, who it seems was at his trade betimes, and mending his brogues by the side of the ditch ; that the spirit of the air, anxious to escape from the prying eyes of mortal wight, leapt from the bank, and, in his haste, dropped both shoe and hammer: if I go on to tell you, that this story is most gravely related, and that the editor informs the public, that both shoe and hammer were carried to such a house, in such a street, in a certain town, in the county of Roscommon, and may there be viewed by any curious or incredulous persons; you will, I think, acknowledge that my tale has at least a better foundation than many which are related to our disadvantage, and but too readily

swallowed by the credulity of our English friends.

A final reference – though there must be many, many more out there:

– might be to the fairy coffins found on Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh in 1836.

Pixy Music on Dartmoor

Books

Hall, Alaric Elves in Anglo-Saxon England (Boydell 2007). Anyone who reads around the fairies will quickly establish the surprising mediocrity of academic books in the field. This is a recent exception. The author is rigorous and demanding both of his readers and his sources. Certainly, the few early texts relating to ‘elves’ in Anglo-Saxon England and, indeed, through the Germanic continuum are whipped over one hell of an obstacle course, while there are also plenty of glances to later fairy and witchcraft texts. There is much to wonder about here, some things to disagree with, but there is no question that this book has set a new standard for the study of early medieval fairies. It was time…

Harte, Jeremy Explore Fairy Traditions (Loughborough, Heart of Albion Press 2004). Type in ‘fairy’ and ‘history’ into Google or Amazon and this book will not come up in the first ten. In fact, it will very likely not come up in the first hundred. It is though the best modern book written on the British and Irish fairy traditions and for Beach the best book on this list. Again, it is proof of an important rule namely that ‘fairy studies’ is one of the few areas where the dilettantes are better than the ‘professionals’. Jeremy Harte has a foot in academia, he publishes in journals and works in a museum. But he is too fresh and original to be contained in a modern faculty building. How many senior lecturers, for example, would argue the rights and wrongs of building on fairy ground from the point of view of the elves!? Kudos, Jeremy.

Mac Manus, Dermot The Middle Kingdom: The Faerie World of Ireland (Colin Smythe LTD, London 1973). A little known book describing fairy belief in Ireland in the late nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century. DMM was a friend of Yeats and himself a believer in fairies and pulled together here a series of peculiarly vivid accounts of rural fairy sightings at the end of Anglo-Irish ascendancy and then as De Valera’s Catholic ascendancy was shaking the last breaths out of the sidhe. The constant references to grandfather’s gardeners, cousins, friends, friends of friends is peculiarly Irish pre or post partition: the island is small, after all. But there is none of that saccharine nonsense (‘they had lovely rainbow wings…’) that infects later works on fairies: this is the only work on this list that will give you nightmares.

Purkiss, Diane Troublesome things: A History of Fairies and Fairy Stories. DP is only our second academic on this list though you just have to read three paragraphs to realise she is an unusual one: nb this book goes by several titles. Her breezy tour through fairy lore from antiquity to Barrie is also at many points controversial. But she is one of these rare individuals who troubles to go back to basics on everything. The results is that, while reinventing some curious-shaped wheels, she gets closer to the essence of things or at least gets at that essence from unexpected directions. This freshness is there in her fairy aphorisms, it is there in the prose – DP is with Briggs the best stylist on this list – and it is there in her maverick judgement calls. Viva Diane!

Spence, Lewis The Fairy Tradition in Britain (Rider 1948). LS was by any standards a strange writer. He dedicated, for example, years of his life to proving the existence of Atlantis with reference to Irish and Mexican mythology: don’t do it, Lewis! Of all his meanderings, his work on fairies has survived best. There is though here a misfortune. It is his other fairy book on Fairy Origins, a stimulating but eccentric monograph, which is endlessly reprinted. Whereas The Fairy Tradition, perhaps the best general introduction to the fairies, is rare. In Spence’s mind this was his ‘source’ book. And while The Fairy Tradition is never tedious the sheer bulk of information can rather clog up your brain. Still there is nowhere else where you can get such a concentration of information in so few pages.

Evans Wentz, W. Y The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries (Oxford 1911). An early incarnation of the ‘pretend’ academic whose writing trumped all those pre-war dry-of-dusts we can no longer remember. Evans Wentz decided after a few terms at Oxford, c. 1908, that fairies were for real. He travelled around the Celtic fringe from the Hebrides to Brittany, against all odds enlisted five major Celticists to help him, and then offered a series of folk lore accounts from the last generation of believers in the rural west. His explanation for what fairies are matter rather less: there is the stench of mid-late-spiritualism about. But the earlier part of the book has, instead, the aroma of burning peat. A lovely work, full of fairy gold.

Briggs, Katharine A Dictionary of Fairies (Penguin, London 1977). Katherine Briggs is the grand dame of twentieth-century fairy writing. A scholar, a storyteller – her interest in fairies was sparked when her girl guide troupe began asking awkward questions – and a gentle-lady of that kind that came out of the Edwardian middle classes. KB wrote five remarkable books and several other interesting ones, but this has to be the most important and the one that will still be read in a hundred years. An encyclopaedia of different fairy types and more importantly fairy questions from ‘Abbey Lubber’ to ‘Young Tam Lane’. This is the kind of book that you can just pick up and flick through when the brown study is upon you. But it is also the one you run to before saying something rash in print. In short, a source of entertainment AND a reference guide: only Brewer’s Dictionary of Fable and the 1911 Encylopedia Britannica can compare.

Fairy Sighting on Skye, c. 1880

A favourite witness account of the ‘good folk’. This was written out in the early 1960s that puts the experience back c. 1880.

In the darkening of an Autumn evening over eighty years ago a little boy in the Isle of Skye was awaiting the return of his mother from a visit to an ailing neighbour. He and his elder sister had been left with their grandmother while their mother was on an errand of mercy. Another little boy had joined them, and all had played happily during the afternoon. Their own home was some distance from their grandmother’s – just too far for little ones unaccompanied. Presently there came to call on their grandmother an elderly woman from the village, one whom the children knew well and whom they liked. Probably by this time they were becoming a little tired and cross, and their old friend was trying to amuse them. Suddenly she said: ‘Come with me. I want to show you something.’ They all took hands and went out into the gloaming and down the path by the side of the burn. Then the old lady stopped, and said: ‘Look, do you see them?’ And there on the hillside, all dressed in green, were the fairies dancing in a ring round a fire. The children were simply enchanted by what they saw, and one can imagine their excitement and the wonderful story they would have to tell their mother on her return. Next morning they rushed out to look for the ashes of the fairy fire, but there was nothing to be seen.

So what is so special about this account recorded in Katharine Briggs’s work?

[A]s children my brother and sisters and I were never tired of hearing this story.

My aunt too, when she came to visit us, would corroberate [sic] the tale. And I have passed it on to mine, and shown them the green, grassy mound ‘where Papa saw the fairies’. Two years ago, and for the first time, I met the third child, now an old man, and he could recall as vividly and clearly as if it had been yesterday all the details of that wonderful evening.

This could in part be rationalised away as brother and sister retelling and retelling an experience and misunderstanding the presence of fairies on a Scottish island: the wealthy Briggs family had connections with Skye. But KB’s discussion of the tale with ‘the third child’ suggests someone outside the magic circle who had his own independent memories. Perhaps KB is right, if we want to look for a ‘rational’ solution, to concentrate on the one adult present who was said to have second sight.

An interesting point in this narrative is the second-sighted woman who gave the children their glimpse of the fairies. It is noticeable that they were all hand in hand when they saw them, though her method was simpler than that of the wizards described by Kirk, who put their right hand on their pupil’s head and their right foot on his left and made him look over their right shoulder. The fairies were dressed in the usual manner in green and were dancing round a fairy knoll, but it was somewhat unusual for them to dance round a fire instead of being more mysteriously lit. Fires are as a rule only used by the iron-working fairies.

Ever heard of the spectobarathrum,

a late nineteenth century machine capable of ‘parting the veil of Faery’

Apparently the inventor, Neville Collmore, actually lectured with these slides:

oh to have been there in and among the theosophists and the circus folk!

There is, of course, a long history of fairy photographs, though none original as these fatagravures.

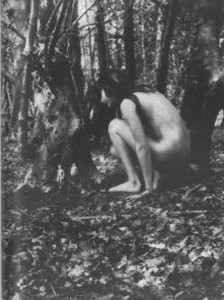

There is also this picture said to have been taken in a witch’s coven in Devon or Cornwall. It is not easy to date on present evidence, guessing post war. Follow the gaze for the little people.

Then while not strictly ‘fakes’ there are a series of late nineteenth, early twentieth century pictures of fairy gadding about: that remind us of the unusual charge that fairies were taking on.

What is the girl doing to the tree trunk?

Cottingley example

In more recent times, 2007, magician Dan Baines created a fairy mummy that was

‘discovered’ for an April Fool’s Joke and then sold on ebay for a bargain 280 pounds sterling.

The elves were Anglo-Saxon fairies and as such deserve a bizarrist’s respect.

They are though – not unlike the medieval fairies that come after – gone almost without trace.

But there is, every so often, a Dark Age charm,

a riddle, a line of Anglo-Saxon poetry that recalls belief in this receding people.

Case of the Cottingley Fairies

Joe Cooper, The Cottingley Fairies, 1990.

The story is a simple one. In the First World War a young girl named Frances Griffith saw fairies at the brook where she played in the Yorkshire village of Cottingley. In 1917 she and her older friend Elsie Wright were stung by their parents’ refusal to believe Frances. They, therefore, went out and photographed a number of cardboard cut-outs of fairies and challenged their elders and betters with the pictures that they had created. The pictures would have, should have sunk without trace but by chance they found their way into the hands of local theosophists who publicised them. The children were encouraged to take more photographs in 1920 and, in fact, under considerable pressure to perform, they produced a further three.

Here still the girls might have got off the hook had it not been for Arthur Conan Doyle. At the end of 1920 the creator of Sherlock Holmes wrote a long article for the Strand Magazine publicising the photographs and writing as if he very much believed they were genuine. The girls became nationally, even internationally known and it is sometimes said that the five photographs that they took are the most reproduced in the history of photography. After a long silence in 1965 the girls, now in their sixties were interviewed again by the press and they were interviewed again periodically until 1982 when finally the truth came out in painful circumstances.

(This is the only photo in the set that is claimed to be real)

It must be extraordinary for the single most important thing to happen to you in your life, for that thing to be, well, a lie. And yet from their teens up until when they finally confessed Frances (who always claimed that she had seen fairies) and Elsie lived that lie as best they could. By the time that Conan Doyle had made them famous, there was no way out except to go down the tunnel, looking neither left nor right, and hoping that they would not be turned into pariahs by the goading journalists and adulating groupies around them.

This book then is about a life-long ordeal: a multi-jawed, poison-edged monster trap that would have defeated most of us and that was quite too much for two little girls who strayed too far into the undergrowth. Who says that fairies are no longer frightening? The author, Joe Cooper, who, himself thinks that fairies exist and who for many years defended the photographs knew both women. It was he, in fact, who finally brought the truth out in circumstances that perhaps do not do him the greatest credit. Both Frances and Elsie cut all contacts with him after he went public.

(A modern interpretation)

By reading through JC’s sympathetic version of events we come as close as we ever will to understanding how people ever thought that these photographs of suspiciously Edwardian-looking fairies were genuine. When Beach showed Mrs B the photographs, she shook her head and noted that they were obviously cardboard cut- outs: she certainly could not understand why anyone would trouble writing a book about them. But many millions wanted them to be true, collectively answering the pantomime voice ‘do you believe in fairies’, trying to keep the fey alive in a world that was rapidly growing tired of them.

In many ways The Middle Kingdom is the younger brother of Evans-Wentz’s The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries (1911). Certainly, they have something important in common. Their authors were intelligent men who believed in fairies. However, in the case of Evans-Wentz his belief was the result of a flirtation with theosophy and is the forced account of an outsider. Mac Manus though seems much more at ease with the fairies, at least Irish ones. He describes a series of encounters that he had personally verified and that included experiences of his own family members – his great grandfather once, for example, foolishly moved a fairy tree. True there is some cross-pollination from what might be called late-theosophy. Mac Manus was a friend of Yeats and sometimes his vocabulary betrays a rather unIrish way of seeing things: one fairy is put down as an ‘earth elemental’, whatever that is.

There are chapters on ‘Pranks and Mischief’, ‘The Stray Sod’, ‘Hostile Spirits and Hurtful Spells’, ‘Fairy Ground and Paths’, ‘The Pooka’ (with some enjoyable nonsense about cigarette cards) and a concluding chapter on ‘The Problem of Reality’.

The author is not a folklorist in any normal sense, nor is he, at least in this book, a historian,

But he is a gifted raconteur and many of the tales he has amassed leave a chill as ‘true’ fairy tales should.

Clonmillan Hill has always had a reputation for being connected with the fairies, including the great Shee as well as the lesser Shee-og… The two girls had not got halfway up when the boys who had only gone on a short distance down the Mullingar Road, heard them call out. When the lads looked back they saw that the girls had stopped and were looking earnestly into the field on their right. After a few moments they saw the girls turn back and run down the lane on to the main road again. On reaching the road, the girls went over to a gate opposite the lane and stared into the field beyond it. Then they began urgently beckoning to the boys to join them there. They boys, who were thirty or forty yards away, ran up at once, little dreaming what an extraordinary thing they were about to see.

Whey they joined the girls at the gate and looked through it, to their utter astonishment they saw, some forty yards away, a group of dark figures of human size standing in a circle about ten yards in diameter. Black capes or shawls were draped over their heads and hung across their shoulders and from there dropped straight down to or into the ground, but with no crease or bend where they reached it. The figures stood so close together that their draperies touched from the shoulders down, making it impossible to see past them. They were quite motionless, even to folds and pleats of their draperies, as if carved out of some black stone, and their heads were erect. Mr Gowran [one of the boys grown up] says emphatically that these black cloaks were not woollen but were made of some very fine cloth that was not shiny, and so could not have been silken either.

Another remarkable feature was that the whole centre of the circle of figures appeared to be covered by a black cloth at the height of their shoulders. From it rose what seemed to be a chest – or though the children did not think of it at the time, a coffin – and it, too, was covered by the same black material, which lay snugly on the chest and showed its shape clearly. The top of the chest was a foot or a little more above the heads of the surrounding figures. And on the top of this chest lay a set of old Irish bagpipes. Mr Gowran can still describe them in detail and can remember just how they lay. There were three drones each about three feet long, one of which lay towards him and the other two away from him. The bag and the mouthpiece hung down over the side of the box. The drones were of unusual shape and were as thick as a big man’s wrist.

The children had stood looking at this curious sight for a considerable time, probably two or three minutes, when they saw Dan Jackson, the owner of the field, and his eighteen-year –old son approaching from the field beyond it, which was divided from it by a small ditch and strolled unconcernedly on. It seemed as if they were going to walk up to the figures, but it was soon clear that neither of them saw anything unusual, and after passing within six feet of the dark silent figures, they approached the gate.

Afraid of being asked awkward questions, and being rather alarmed at what they saw, the four children ran off towards the town just before the two men reached the gate. But the two boys, being bolder than the girls, stopped after they had gone a short distance and peered through the hedge again. They were now alongside the next field and so had to look through the side hedge as well, but they found a gap and saw that the mysterious figures were still quietly standing, but the circle had moved some ten yards further away and was now close to the ditch of the next field, covering the track along which the two men had just passed.

Endless reading in the literature of fairies has led to a couple of unusual passages.

The first is from a south-western fairy tale where a man is reunited with his ‘dead’ fiancé who is actually trapped in fairy land. While there she explains the lifestyle, beliefs and manners of the fairy folk.

‘For you must remember they are not of our religion,’ said she, in answer to his surprised look, ‘but star-worshippers. They don’t always live together like Christians and turtle-doves; considering their long existence such constancy would be tiresome for them, anyhow the small tribe seem to think so. And the old withered ‘kiskeys’ of men that one can almost see through, like puffs of smoke, are vainer than the young ones. May the Powers deliver them from their weakly frames!

And indeed they often long for the time when they will be altogether dissolved in air,

and so end their wearisome state of existence without an object or hope.’

This is Robert Kirk on the fairies in his Secret Commonwealth,

written in 1691 describing fairy beliefs.

They live much longer than we yet die at last, or least vanish from that state.

For ‘tis one of their tenets that nothing perisheth, but (as the sun and year) everything goes in a circle, lesser or greater, and is renewed and refreshed in its revolutions,

as ‘tis another that every body in the creation moves (which is a sort of life),

and that nothing moves, but has another animal moving on it, and so on,

to the utmost minutest corpuscule that’s capable to be a receptacle of life.

Fae

Recently stumbled on a rather beautiful book about Yorkshire in the late nineteenth century,

one that offered up a page or two on the gentry. The passage begins with some fairly bog standard stuff about how there is still the memory of fairies among the commoners.

A correspondent from the borders of the North and West Ridings tells me of the strong belief in fairies that existed among the people of his district when he was a boy. It seems he used to talk to an old inhabitant who, as he confessed, had often ‘seen the fairies. Figures of men and women gaily clad, of full size, and in rapid confused motion, he said he had often watched in early summer mornings. He used to tell of an unbelieving horse-dealer who had stayed the night with him. At dawn the old farmer saw the fairies, as he had so often done before, and called up his guest, who, unbeliever though he declared himself to be, hurried out as he was, very lightly clad, and sat so long on a wall watching them that he caught a rheumatism that he never was cured of.

By the way, a young woman, into whose house this same gentleman once went, told him that she had never seen fairies (though her relations often had) but she had smelt them. On his asking what sort of odour he was to expect so that he might be similarly favoured, she went on to enquire if he had ever been in a very crowded ‘place of worship’ wherein the people had been congregated for a length of time. Such was the description; a very different one had been looked for; but it is the unexpected which happens.

the fact that the nineteenth-century Protestant Welsh believed that in fairy matters any sufferer should make a bee-line for a Catholic priest. While musing on this Beach came across the following bit of bizarreness from the second half of the nineteenth century, from the most bizarre corner of the United Kingdom, Strabane in the Six Counties. Today confessional warfare involves collecting money for one group or other of sectarian thugs and occasionally throwing stones at the police. A century and a half ago there was also though a fairy front!

Fairy Death Bed Conversion

John McCorkle, the dying man, aged eighty, was all his life a Presbyterian. He lived in a house by himself, being attended by a woman who is a Roman Catholic. The Rev. Jas. Gibson regularly visited him, and entertained a favourable opinion of the old man’s piety. He was also frequently visited by one of the elders. On Sunday the 22nd ult.. Mr McCorkle sent word to Mr Gibson that he was very ill, and requested to be remembered in the prayers of the congregation; soon after his mind began to wander. He accused the fairies of having shot him through the head, and he mentioned the name of Mr Magee – the [Catholic] priest – as having power to save him from their influence. On being asked, he said that the suggestion had come from ‘that woman there’, meaning his Roman Catholic servant.

Mr Magee was afterwards summoned by the woman in Mr McCorkles’s name. He came at once, and began his ministrations before any of the old man’s relatives, who are all Presbyterians, were aware. An old neighbour woman, a Presbyterian, came in, and was astonished to see the priest at the bedside. She told him he must have made a mistake, and requested him to withdraw. He told her he had been sent for, and refused to withdraw, but ordered her to leave the house. She at length ran and acquainted the sick man’s relatives. One of them, a respectable young woman, ran in and ordered the priest to desist. The priest seized her by the arm roughly, and forcibly expelled her, barricading the door. A male relative soon arrived and forced the door open, so as to be able to see the priest, and warn him to desist. Mr Magee put his head out of the door and ordered a Romanist, who was passing, to put the man away. This he did speedily and violently. A Romish crowd also collected to protect their priest from interruption. Mr Magee, on Sunday evening went to a magistrate and made an affidavit, in which he swore that he had been sent for by Mr McCorkle, that he had found him quite sensible and anxious to see him, but that he apprehended personal violence in case he attempted to repeat his visit, and therefore claimed the protection of the constabulary. This was granted, and shortly after eleven o’clock at night he proceeded again to the house, accompanied by a number of armed police and a crowd of Romanists. All the sick man’s relations but one, a young man, had gone home. The priest ordered his friends away. This was done, the door closed, and the priest finished his work. McCorkle was made a Romanist, and died a few hours later ‘a good Catholic’.

Placenames

But among these precious glimpses of English fairies before the Normans there are the most durable proofs of all: placenames. For a number of English placenames hint at elf-belief among the general population. It is admittedly difficult to distinguish elf-names from other kinds of names. For example, the elf-sounding Elvington in Kent was – the earliest forms of the name suggest – Aelfgyth’s Tun, an estate belonging to an Anglo-Saxon woman named Aelfgyth: ‘aelf’ was frequently found in both men and women’s names. In other cases, there is the danger of confusion between elves and, believe it or not, swans, elfitu (sigh).

But even given this a few names make it through to the elf-approved category and perhaps the most exciting of these is Elveden, a village on Suffolk side of the Suffolk-Norfolk border. Eleventh century forms, the earliest we have include: Haluedona and Eluedene that look rather like the Elf-denu or the Elf-valley.

Normally, with placenames this bare act of reconstruction is all that we can actually do, hoping that the Domesday Book’s scribe was being attentive. But, in this case, there is something else.

A twelfth-century saints’ life seems to records Elveden in Latin: ex rure… quodam beatis regis et martyris Edmundi quod lingua uallem nunpharum interpretatur anglica, ‘from the lands of the king and martyr the blessed Edmund, which is called valley of the nymphs in English’. St Edmund is, of course, the East Anglian king and victim of the Vikings and Domesday confirms that Elveden belonged to the abbey of St Edmund. Nymphs was an English approximation then of elves. [Alaric Hall, 64-65]

If the life in which this quotation appears – Miracula sancte Wihtburge – is really twelfth century then we either have a folk memory of elves peeping through the leaves or an inventive hagiographer who has decided to ‘interpret’ a place-name.

Known as The Hel stone

To the north of Humberstone village, next to a roundabout and close to the Porsche Garage, is a standing stone – Leicestershire’s only ancient monolith known today as the Humber Stone’ Throughout history the stone has gone by many names, Humber Stone being the most recent, named after the closest village. The village being named after the stone is a common misconception.

We actually know that Humberstone church had a passageway to the nearby (but now demolished) Monk’s Rest, but we don’t know if there’s a tunnel beneath the Humber Stone itself. But that’s not the only reference of a tunnel at the stone. Another legend speaks of a subterranean chamber that linked the Humber Stone with Leicester Abbey, but again such a tunnel has never been discovered.

If the village was named after a powerful prince, and if the landscape was ceremonial to the Vikings, there should have been some sort of ceremonial structure, or centre of worship, in the village. Failing that there should surely be some kind of archaeological evidence for their existence.

The north side of the tower has three, more whimsical images. There is a hare chasing a dragon and a forest creature covering another depiction of the hare. The central relief appears to be a hunting scene – a man blowing a horn, leading a pack of dogs or wolves as they chase a wild boar. Separating each frieze is a small square of darker coloured stone, each displaying a bird of some description.

On the east side are more decorative freizes, separated again by two square, black stones, this time displaying the famous image of the star and crescent.

Norse in origin? Well, after looking through Scandinavian myths and legends every relief can be interpreted. Some fit into Christian myths, some fit into Anglo-Saxon myths, some could be interpreted as Norman, but not all of them. When you wade through Norse mythology, each scene can be interpreted as an important Scandinavian myth.

The Wild Hunt is an ancient folk myth prevalent across Northern, Western and Central Europe. Most ancient cultures tell a variant of this legend but the one that fits perfectly with this relief at Humberstone is the Norse myth.

It was known as Odin’s Hunt. Odin is a major Norse god and leader of the Asgard – one of the nine worlds of the Norse religion and the country or capital city of the Norse gods. The ‘Poetic Edda’ is a collection of Old Norse poems, primarily collected in Iceland, which records Odin’s Hunt in fine detail.

There is, however, an alternative theory to the hunting scene. In Norse mythology, the story of Ragnarok is a series of future events, including a great battle foretold to ultimately result in the death of a number of major gods including Odin, Thor, Freyr and Loki. It told of a series of natural disasters and the subsequent submersion of the world in water. Afterward, the world is said to resurface anew and fertile, the surviving and reborn gods will meet and the world will be repopulated.

There are two almost identical images of the ancient star and crescent symbol on the eastern sideof the church tower. These, like the two cockerels/roosters, are almost square in shape and look to be made of the same, darker stone.

The star of the symbol is eight-pointed, sitting above a crescent moon. The eight-points is an important observation as this is a common way the ancient people portrayed the planet Venus, one of the brightest stars in the night sky. Eight is the number of years it takes the planet to return to the exact same point in the zodiac on the exact same date and hence

Venus has been portrayed as an eight-pointed star throughout history.

On Humberstone church, the eight-pointed star is above the crescent moon, which, due to this Old Norse myth, could well represent the boat that carries Aurvandill. The river could well represent the Milky Way, which looks like a river flowing across night sky. The Milky Way and has often been associated with rivers and oceans in world mythology. Whilst Aurvandil was inside the boat, Thorr broke off his frozen toe and cast it into the heavens, above the boat. Many scholars have associated Aurvandil’s toe with the planet Venus, and now, thanks to this carving on Humberstone church, we can now say that the boat represents the crescent moon in the myth. When in conjunction, the crescent moon and Venus is an utterly breathtaking sight and it is no wonder the Viking writers created a myth once this heavenly sight was viewed.

Love & light

Trace

xoxo

No comments:

Post a Comment